Historical Teochew Opera Scripts

The history of Teochew vernacular writing goes back at least five hundred years. We know this because of historical Teochew opera scripts (劇本 giah-bung) that have survived to the present day. These scripts are rare examples of Chinese regional languages (“dialects”) in written or printed form. Some of these books have been digitized and can be read online. However they can be difficult to read because they are laid out very differently from modern books and playscripts. The written language is also unfamiliar to most modern readers, because there are many variant or simplified characters, as well as vocabulary and grammar not found in Mandarin or literary Chinese.

Here we will list the historical editions and any reprints, digitizations, or transcriptions that we are aware of, and also provide a short explainer on how to read these texts.

List of historical Teochew opera scripts

Historical opera scripts include both hand-written manuscripts and printed books. These must have been popular and widely circulated because they were commercially printed and sold to the public. However, only a few examples survive today, mostly in collections outside of China.

Five of the editions below have been reprinted in a facsimile edition, 《明本潮州戲文五種》(Five Teochew opera scripts from the Ming era, 广东人民出版社, 1985). Because two of these editions each contain two different plays printed together, there is a total of seven plays. Fortunately for those of us who are unable to find a copy of this valuable reprint, several of them are now available as digitized versions online, which are linked below where available. In some cases, the digital scans are in color and of high quality, capturing more detail than the printed facsimile.

The Taiwanese scholar Wu Shouli 吳守禮 has published critical editions of Minnan opera works, including some of the works listed below.

《劉希必金釵記》 • Lau-hi-bik Gim-toi-gi • Tale of the Golden Hairpin

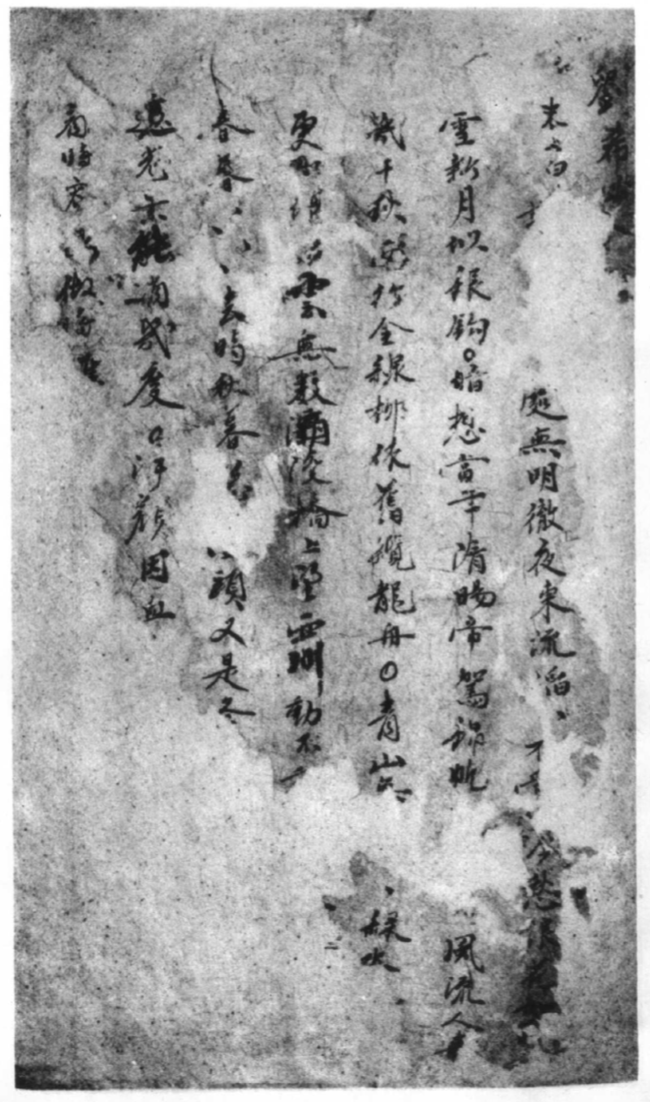

Manuscript, dated year 6 of the Ming Xuande 宣德 era (1431), recovered in an archaeological excavation in 1975. In the collection of the Teochew Municipal Museum.

Photographic reproduction in 《明本潮州戲文五種》 (source for the image below).

Scholarly edition with extensive introductory chapters: 陈历明《潮州出土戏文珍本〈金钗记〉》(广州人民出版社,2012)

《蔡伯皆》 • Cua Bêh-gai

Manuscript dated to the Ming Jiajing 嘉靖 era (1521-1567), recovered in an archaeological excavation in 1958. In the collection of the Guangdong Provincial Museum.

Photographic reproduction in 《明本潮州戲文五種》.

《荔鏡記》 • Li-gian-gi • Tale of the Lychee and Mirror

This opera is also known as 《荔枝記》 Li-gi-gi, “Tale of the Lychee Branch”. The modern opera 《陳三五娘》 Dang-san Ngou-niê is based on the same story. The story is partly set in Quanzhou 泉州 (Tsuann-tsiu) and Teochew prefectures, and a version is also performed in Quanzhou / Hokkien opera. As a result, this opera has also been claimed as part of the heritage of Hokkien-language opera, and is one of the “Four Great Works” of Taiwanese 歌仔戲 kua-á-hì opera.

Several historical editions have been rediscovered, suggesting that this was a popular story, frequently adapted and re-printed. The oldest known editions are from 1566 (below, left) and 1581 (below, right).

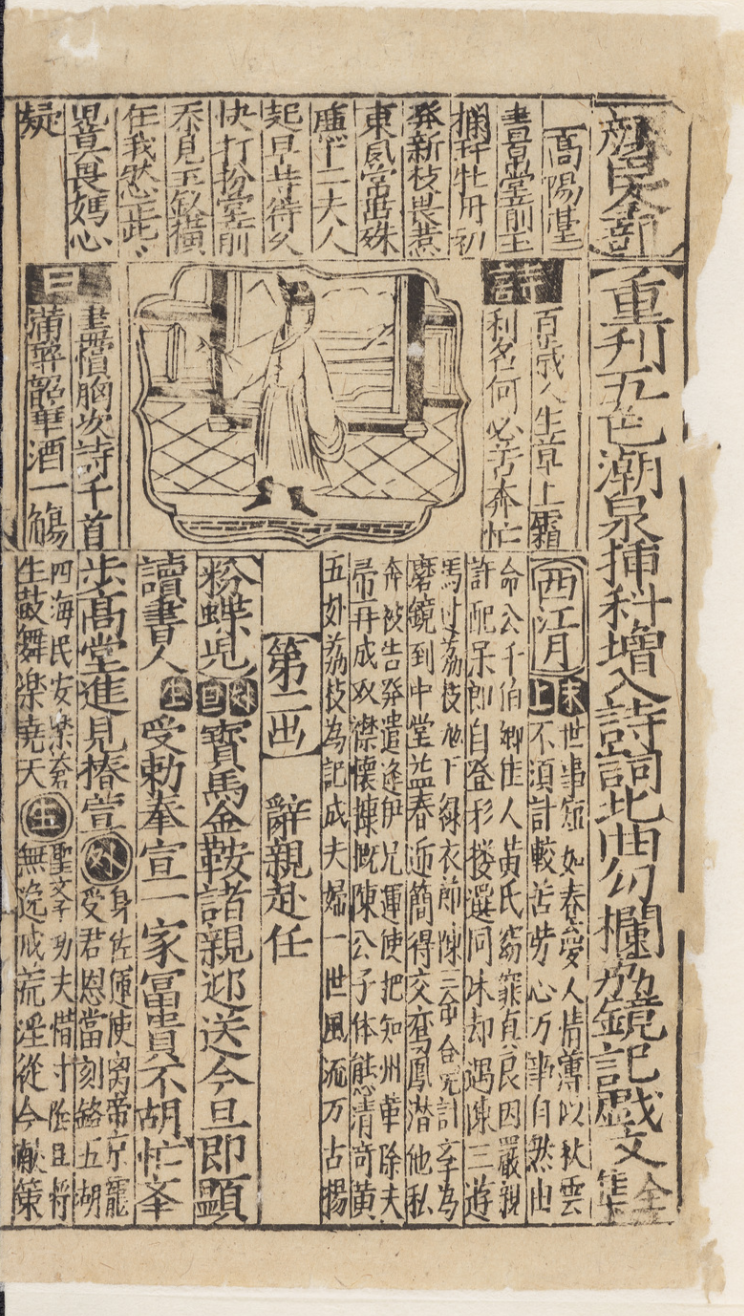

Ming Jiajing 嘉靖 version of 《荔镜记》 (1566)

Full title:《重刊五色潮泉插科增入詩詞北曲勾欄荔鏡記戲曲全集》Published in year 45 of the Ming Jiajing 嘉靖 era (1566). There are two known copies, one in the Bodleian Library of Oxford University, the other in the Tenri Library, Japan. The Bodleian copy was rediscovered in the 1930s by Xiang Da 向達.

This version is a mixture of Quanzhou 泉州 (Tsuann-tsiu) and Teochew source editions. The text is printed together with excerpts from a Minnan play 《顏臣》 Hian-cing, and excerpts and arias from other plays; the Li-gian-gi text is in the lower register of each page.

Critical edition: Wu Shouli 吳守禮《明嘉靖刊荔鏡記戲文校理》,從宜出版社,2001年12月,ISBN 9869997481

Available reproductions:

- Photographic reproduction in 《明本潮州戲文五種》, based on the Tenri Library copy.

- Digital scan, Oxford University Bodleian Library Sinica 34/1 and 34/2 (in color and higher resolution than the printed reproduction, source of the image above.)

- Digital scan, Peking University Library facsimile edition, via Internet Archive; this scan appears to be based on the copy held in the Tenri Library, Japan.

- Transcription, Academia Sinica Southern Min Archives database

- Transcription with notes by Wu Shou-li 吳守禮 and recitation in Zuan-ziu pronunciation by Li Limin 李麗敏, hosted by Taiwan Ministry of Culture

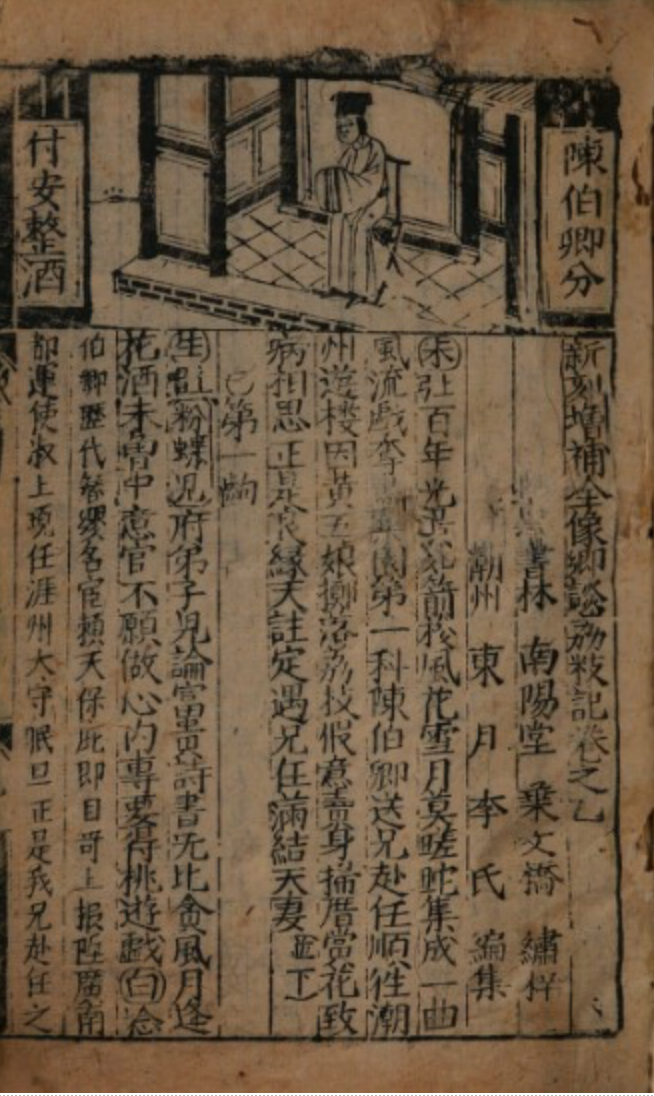

Ming Wanli 萬曆 version of 《荔枝記》 (1581)

Full title: 《新刻增補全像鄉談荔枝記》 Published in the year 9 of the Ming Wanli 萬曆 era (1581). Said to be representative of the Teochew editions; the first page states that it was “compiled by Li Dong-ghuêh of Teochew prefecture” 「潮州東月李氏編集」. Held by the Austrian National Library, rediscovered by Piet van der Loon in 1964.

Critical edition: Wu Shouli 吳守禮《明萬曆刊荔枝記戲文校理》,從宜出版社,2001年12月,ISBN 986999749X

Available reproductions:

- Photographic reproduction in 《明本潮州戲文五種》

- Digital scan, Austrian National Library (in color and higher resolution than the printed reproduction, source of the image above).

- Transcription by Learn Teochew

Other editions

Later versions of this play have also been preserved, and more may be rediscovered in the future. However these other versions are not available online. If you are aware of a publicly available digitization, please get in touch!

- 《新𢳣潮調陳三泉南錦曲加調全集》

- Cover, preface, and postscript missing but dated to ca. 1600 by comparison to other publications.

- Held by the National Library of Scotland, Advocates’ Library 6.451. This edition was rediscovered in 2019 by a doctoral student at the University of Edinburgh, Wang Yibo. A critical edition is currently in preparation by Dr Wang.

- 《新刊時興泉潮雅調陳伯卿荔枝記大全》

- Published in year 8 of the Qing Shunzhi 順治 era (1651), private collection

- Critical edition: Wu Shouli 吳守禮《清順治刊荔枝記戲文校理》,從宜出版社,2001年12月,ISBN 9869997309

- 《陳伯卿新調綉像荔枝記全本》

- Published in year 11 of the Qing Daoguang 道光 era (1831), private collection

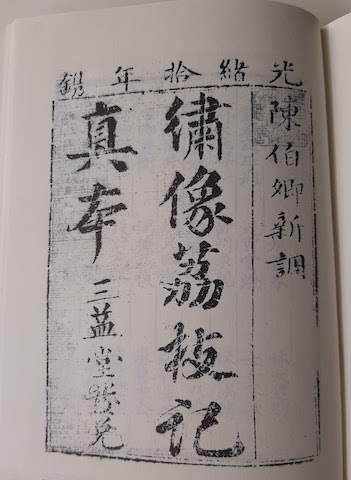

- 《陳伯卿新調繡像荔枝記真本》

- Published in year 10 of the Qing Guangxu 光绪 era (1884); two copies, both held in private collections.

- Reprinted in《俗文學叢刊》第113冊 465-553頁 (民國91年, Taipei: Institute of History and Philology) (above), but this copy is incomplete: chapters after 安童尋主 are missing.

- Critical edition: Wu Shouli 吳守禮《清光緒刊荔枝記戲文校理》,從宜出版社,2001年12月,ISBN 9869997317

《蘇六娘》 • Sou Lag-niê • Sixth Lady Sou

Probably printed during the Ming Wanli 萬曆 era (1572-1620). The text was printed together with another Teochew play 《金花女》 Gim-huê-neng in the same volume (see below). The text of Sou Lag-niê is in the upper register of each page, whereas Gim-huê-neng is in the lower register. The volume was formerly in the collection of Nagasawa Kikuya 長澤規矩也, and is now preserved in Tokyo University (source of the image below).

This historical edition contains a selection of eleven scenes from the play, so there are some logical gaps in the story. The modern opera of the same name is based on the same story, which has a similar theme as Dang-san Ngou-niê, and is also still one of the most popular Teochew operas.

Critical edition: Wu Shouli 吳守禮《明萬曆刊蘇六娘戲文校理》,從宜出版社,2002年7月,ISBN 9574103331

Available reproductions:

- Photographic reproduction in 《明本潮州戲文五種》

- Digital scan, Tokyo University IASA Library D8423400

- Transcription, Academia Sinica Southern Min Archives database

《金花女》 • Gim-huê-neng • Golden Flower Lady

Printed together in the same volume with Sou-lag-niê (see above).

Critical edition: Wu Shouli 吳守禮《明萬曆刊金花女戲文校理》,從宜出版社,2002年7月,ISBN 9574103323

Available reproductions:

- Photographic reproduction in 《明本潮州戲文五種》

- Digital scan, Tokyo University IASA Library D8423400

- Transcription, Academia Sinica Southern Min Archives database

NB: Images on this page are low-resolution copies for illustrative purposes only. Rights belong to the copyright holders. See text for sources.

How to read historical opera scripts

The printed opera scripts were printed and thread-bound in the traditional way. In woodblock printing, an entire sheet of paper is printed from a single carved block. After a sheet is printed, it is folded in half with the printed side facing outwards, resulting in two adjacent pages. A stack of folded sheets is then sandwiched between covers and sewn with thread on the open edges to make a threadbound volume (線裝).

To read these books, you will need some knowledge of Teochew, as well as how the content is laid out and organized on the page:

- How the pages are formatted (layout)

- How the different stage roles and directions are indicated

- What simplified and non-standard Chinese characters are used

The example pages here are from the Ming Jiajing edition (1566) of the 《荔鏡記》 Li-gian-gi, from a digital scan of the Bodleian copy. This edition was published at Jianyang 建陽 in Fujian 福建 province, which was an important center for commercial publishing in the Ming and Qing.

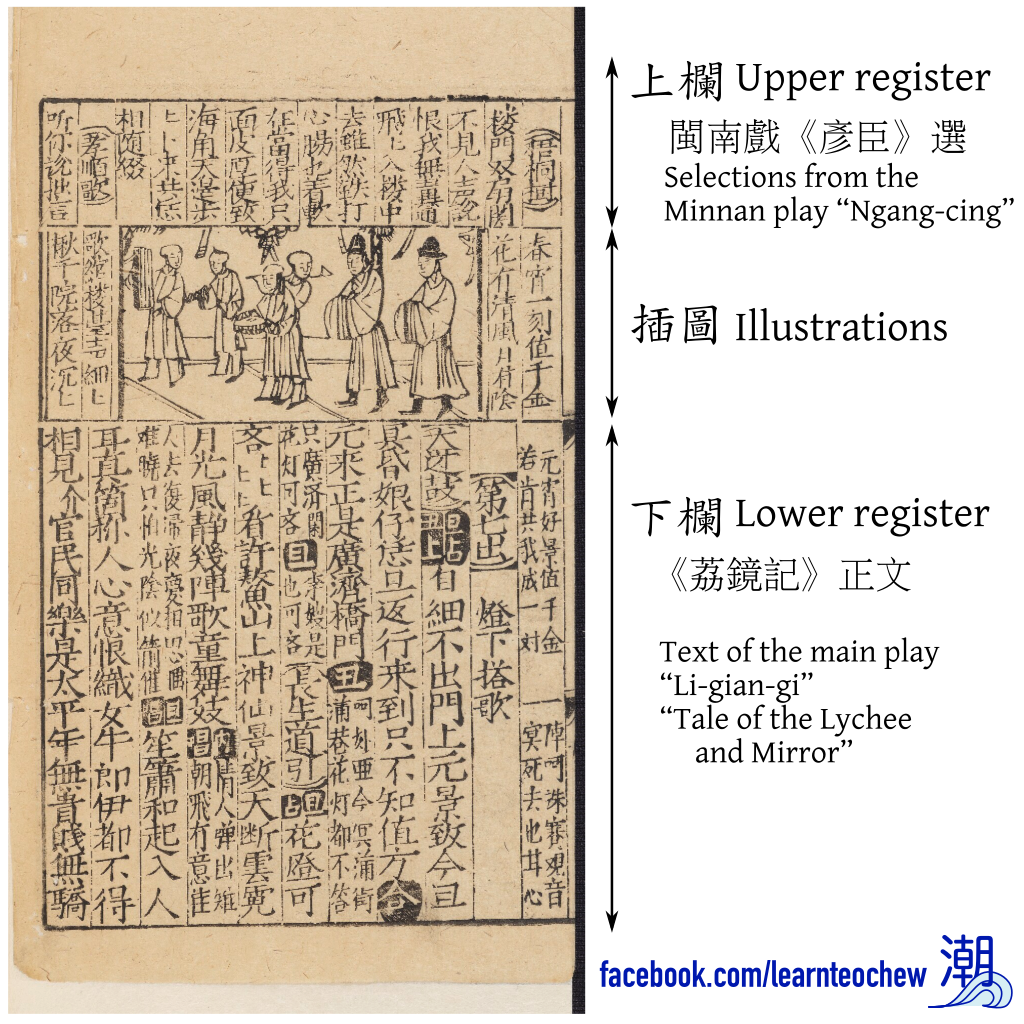

Page layout

Like most traditional Chinese books, the text is in vertical lines, arranged from right to left.

The content on this page is in three horizontal blocks: a smaller “upper register” 上欄 of text (top), illustrations 插圖 (middle), and a larger “lower register” 下欄 of text (bottom). Actually, this volume contains two different works: 《荔鏡記》Li-gian-gi in the lower register and selections from another play 《彥臣》 Ngang-cing in the upper register. Bundling popular works together was a common practice by publishers to make the books more attractive to buyers. However not all books are like this: for example, the 1581 《荔枝記》 Li-gi-gi has only one text register and illustrations.

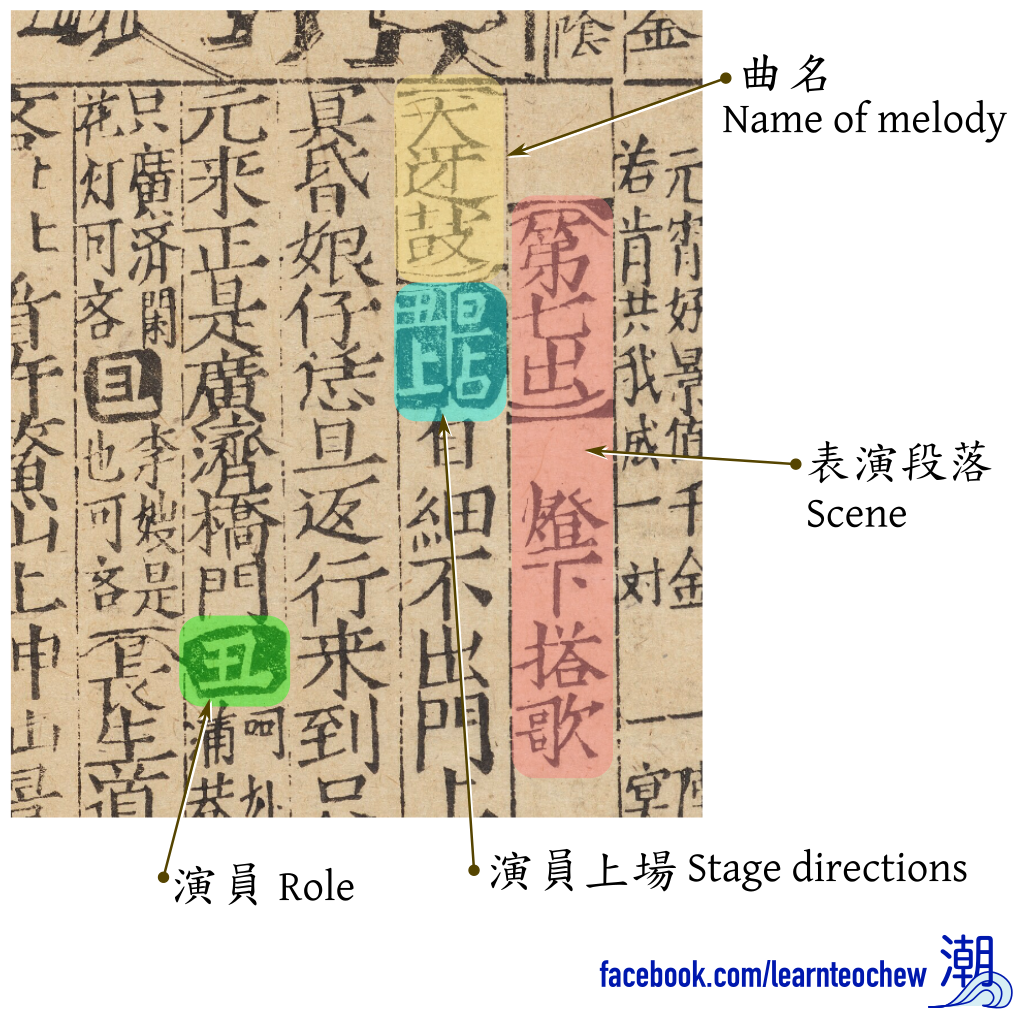

Headings, roles and stage directions

Each scene or act usually has a numbered heading, followed by a title. Here the heading is surrounded by a thick bracket: 【第七出】燈下搭歌 “Scene 7 – joining in song under the lanterns”.

Operas are mixtures of sung and spoken parts. The melody is referred to by name〔大迓鼓〕and surrounded by brackets or otherwise highlighted. The same melodies were used between different operas, just with different words. Many of the melodies in the Li-gian-gi are still preserved today in the Lam-gueng 南管 musical tradition.

This is followed by the stage direction 旦占丑上, meaning that the actors playing the roles of 旦 duan (female lead), 貼 tiêb (female second lead, this book uses the simplified character 占), and 丑 tiu (clown) come on stage. Unlike modern scripts, the characters are not referred to by name but by the actor’s role.

In the Ming era there were seven main roles:

- 生 sêng - Male lead

- 旦 duan - Female lead

- 貼 tiêb - Female second lead

- 外 ghua - Old person

- 丑 tiu - Clown

- 末 bhuah - Middle-aged person

- 淨 zêng - Painted-face

In modern times this has been simplified to four main roles: 生、旦、淨、丑, but each can be subdivided further (e.g. 小生、老生……).

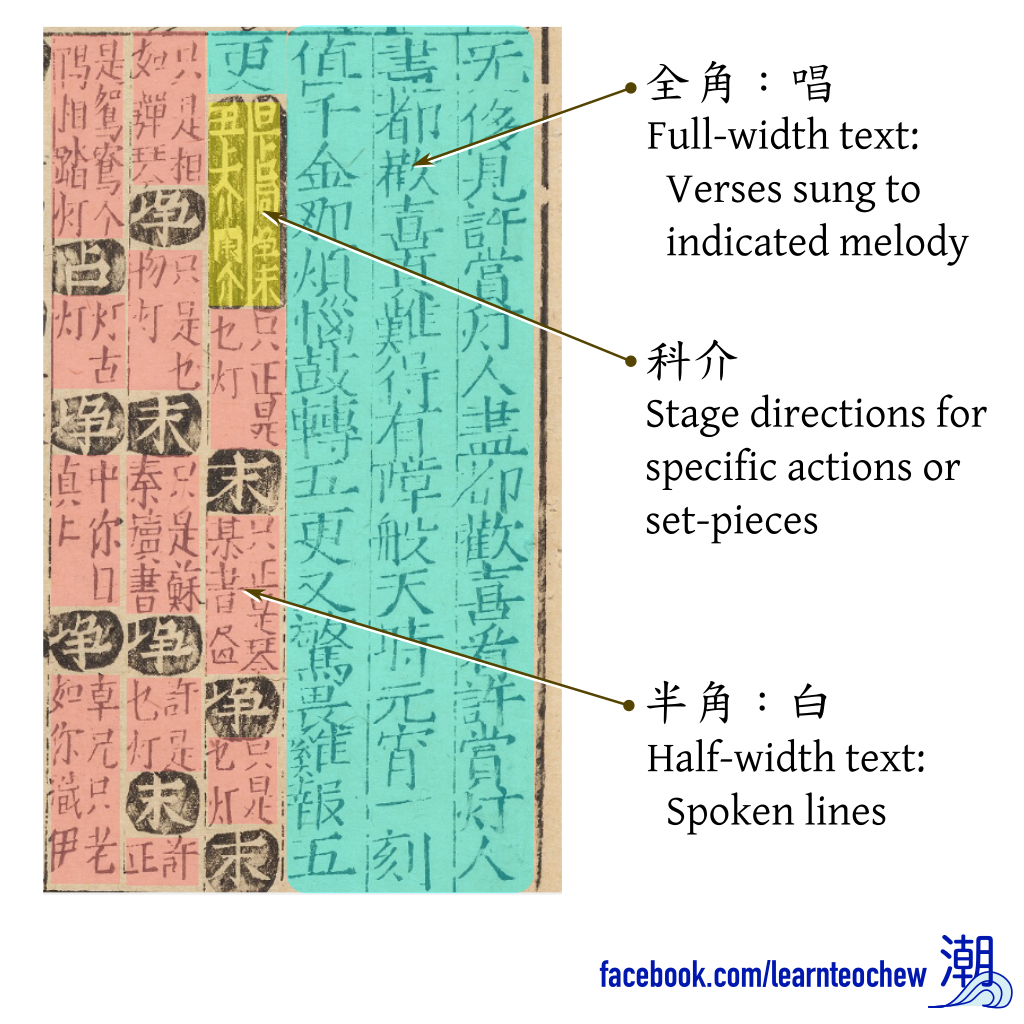

The sung parts are printed with full-width characters, whereas spoken parts are printed half-width.

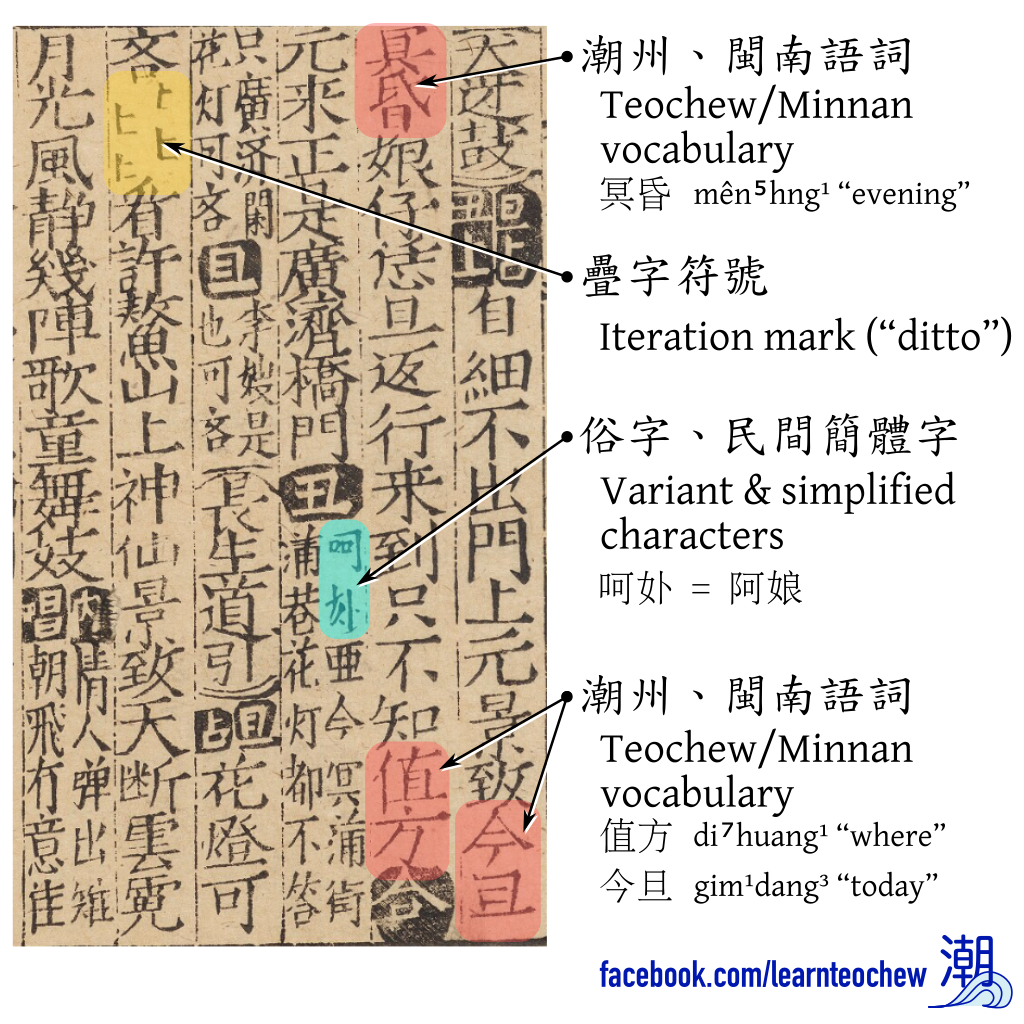

Teochew vocabulary and non-standard characters

Teochew has different vocabulary and grammar from Mandarin or literary Chinese. Although the language used in opera has more literary influence, there are still Teochew/Minnan words or phrases that are not found in Mandarin.

In the excerpt below there are Teochew/Minnan words such as 冥昏 mê-hng “evening”, 值方 di-huang “where?”, and 今旦 gim-dan “today”.

Commercially printed books often used simplified characters because of the expense of block carving. For example, 呵𭑧 is a simplified form of 阿娘 a-niê “Miss”. Such simplified characters were common in handwriting and printed books, although not in official or scholarly publications. Some of were adopted as official simplified characters in the 20th century, but many may be unfamiliar to modern readers.

The iteration mark, which looks like the character 匕, means that the previous characters are to be repeated, much like “ditto” in English.

Further reading

- 饶宗颐,〈说略〉,《明本潮州戏文五种》4–18页,广东人民出版社,1985年

- 曾宪通,〈明本潮州戏文所见潮州方言述略〉,《方言》 1991年 (1) : 10-29

- Piet van der Loon. 1992. The classical theatre and art song of South Fukien: A study of three Ming anthologies. Taipei: SMC Publishing. ISBN 9789576381072

- Lucille Chia. 2002. Printing for profit: the commercial publishers of Jianyang, Fujian (11th-17th centuries). Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series 56. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 9780674009554