Singapore Teochew – Then and Now

Teochew and other Chinese ”dialects” are much less widely spoken in Singapore than in the past. Few young people still speak the language regularly, and those who do will often mix it freely with other languages, especially English and Mandarin. It is no surprise that the language has changed over the years, but how?

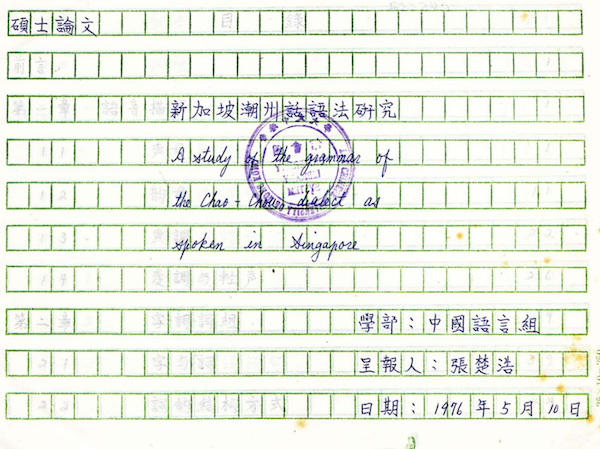

In this post I would like to introduce you to two remarkable student theses, one written in the 1976, and the other in the 2011. Both are available online from their university libraries. Where in the past one would have to make a trip to Hong Kong and Jurong respectively, it is now possible to access them from the comfort of one’s home. Zhang’s 1976 thesis is impressive for another reason: it was written in Chinese in the era before personal computers, and so is handwritten on over 400 pages of 稿紙 (the rows of green squares will still haunt many generations of Chinese students).

Zhāng Chǔhào 張楚浩. (1976). Xīnjīapō Cháozhōuhuà yǔfǎ yánjīu 「新加坡潮州話語法硏究」 (A study of the Chao-chou dialect as spoken in Singapore) (M.A. dissertation). Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong. CUHK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Collection

Yeo, Pamela Yu Hui. (2011). A sketch grammar of Singapore Teochew (Academic exercise). Singapore: Nanyang Technological University. Nanyang Technological University

Both are outline grammars of Teochew as spoken in Singapore. The dates are significant: the Speak Mandarin Campaign is often blamed for contributing to the decline of Chinese “dialects” in Singapore, and it was launched in 1979.

These two works therefore present a before-and-after snapshot of Singapore Teochew in two different eras: the earlier in a time when many Teochew speakers in Singapore were actually born in China and used it as their main, if not only, language at home, and the later one where English has come to dominate public life, and where even Mandarin struggles to maintain its position among younger speakers.

I have not myself read through both of these works completely. However I did compare their descriptions of one topic that interests me: sentence-final particles, also known as utterance particles. These are the “lahs” and the “lohs” that people add to phrases or sentences to express different shades of meaning. They are a distinctive and instinctive part of Singlish: it is hard to explain how to use them, but very easy to notice when someone is using them “wrongly”. Singlish in turn has borrowed this feature from Chinese languages like Teochew, Hokkien, and Cantonese.

Teochew has a rich set of utterance particles (see our pages for more information). They have not been studied as well as other features of Teochew grammar, so there is still a lot to be learned about them.

Zhang (1976) gives over a dozen particles that he classifies into five categories (some belong to more than one category):

- Declarative: liêu 了, lou7 𡀔, li1 哩, dian7 定, huan1 欢, lia6

- Interrogative: nê6, han3, la1 啦

- Imperative: no7, hoi3, ua 哇, li 哩, huan1 欢, han7, a6, la

- Conjectural: nê6, no7

- Pauses: a 啊, li1 哩, nê6

Some of these, such as liêu and lou7, would be better classified as aspect markers rather than utterance particles, in my opinion (see our page on aspect markers).

However in Yeo (2011), only three were reported: la1, lo5, lê5.

Has the set of utterance particles used in Singaporean Teochew become poorer over the years? It is tempting to draw this conclusion, and it would fit with the general consensus that Teochew usage is declining and decaying in Singapore. Yeo’s thesis in 2011 was based on interviews and elicited speech from informants, that she then transcribed and analyzed. Zhang, on the other hand, was a native speaker of Teochew and presumably could draw on his full knowledge of the language, not restricted to a limited corpus of source material. It is therefore possible that Teochew speakers still regularly use utterance particles other than la1, lo5, and lê5, just that they did not have the opportunity to do so in the recordings that were used for Yeo’s research. It is difficult to make an argument from absence of evidence.

What we can observe though is that the particles lo5 and lê5 appear in Yeo’s work but not in Zhang’s. These are also not attested in another earlier work on Teochew grammar, namely Li Yongming’s 1959 book Chaozhou Fangyan, which describes the language as spoken in China.

Yeo notes that:

It would also be interesting to investigate if utterance particles in Singlish have any influence on that in Singapore Teochew or vice-versa since these particles are a prominent feature of Singlish and quite a number appear similar on the surface in both languages.

My guess is that the triad of “lah” “leh” “loh” is so well established in Singlish that they are also used when Singaporeans speak Teochew. Jack Lee’s Dictionary of Singlish suggests that “leh” comes from the Cantonese pronunciation of 哩, which is similar in usage to the Teochew li1.

If so this would be an interesting instance of a “round-trip” word that diverged in China between Cantonese and Teochew and came back together again in the “rojak” (salad) dish that is Singapore.

Both these works contain a wealth of detail and I am sure we will revisit them in future posts.

Posted on 2021-02-04 00:00:00 +0000