Teochew Literature (1) - Tale of the Lychee Mirror 《荔鏡記》

We often hear that Teochew, like other “dialects” are spoken but not written, 有音無字 u6im1 bho5ri7. Therefore, some of us may be surprised to learn that there is traditional written literature in Teochew.

It’s true that in the pre-modern era, most Chinese texts were written in literary Chinese. That was because most writing was done by literati who were trained in this artificial language. However, some texts in the vernacular, spoken languages have survived to the present day.

The Tale of the Lychee Mirror 《荔鏡記》 Li6gian3-gi3 is an opera written in Southern China during the Ming era, around the mid-16th century. The story may be better known as 陳三五娘 Dang5-san1 Ngou6-niê5 (the third son of the Dang5 family and the fifth daughter of the Ng5 family), and is also retold in many folk songs and other operatic adaptations in both Hokkien and Teochew. If you have older relatives who know Teochew opera, they will almost certainly be familiar with these names. It’s likely that the story has been around for a long time, and that 《荔鏡記》 simply happens to be the oldest surviving printed version out of many.

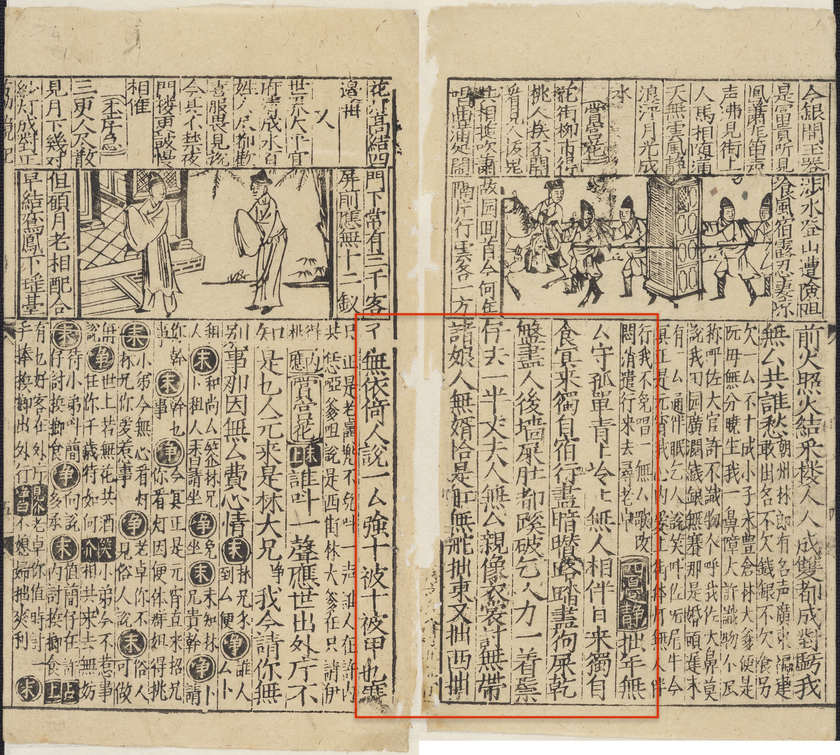

(Photo: © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, reused under CC-BY-NC 4.0 license)

Dang5 San1 陳三 was a scholar and a native of 泉州 Zuan5ziu1 (part of Hokkien province, in Hokkien: Choân-chiu), and while traveling through the Teochew region, encountered Ng5 Ngou6-niê5 黃五娘 during the Nguang5siao1 元宵 Lantern Festival, and the two then fell in love. The rest of the story describes the many difficulties the couple had to endure before they could be together (no spoilers!).

The earliest available editions of the Li6gian3-gi3 date from 1566 and 1581, and are among the earliest texts written in vernacular Southern Min. The play is partly written in Zuan5ziu1 Hokkien, and partly in Teochew. Because the text is written with Chinese characters, it is sometimes difficult to identify the original Teochew or Hokkien words behind them. Sometimes a corresponding literary Chinese word is borrowed to substitute for the vernacular word (semantic borrowing), or characters with similar pronunciation are used to spell out words that don’t have a standard character (phonetic borrowing). Many Teochew vocabulary terms in Li6gian3-gi3 and other Ming-era vernacular plays have been identified in a study by Zeng Xiantong 曾憲通 (1991).

Zeng commented that much of the play is written in a more literary style, but some parts use vernacular language that is close to how people really speak, and which he says would still be understood today. One of these that he annotated in his article is “The Wife-less Man’s Lament”, a song by a man complaining about life without a wife.

There are only a few copies of the play in existence, in different editions dating from the Ming and Qing periods. The latest one to be rediscovered was found in the National Library of Scotland only a few years ago by a PhD student named Wang Yibo (2019), in a book collection that was originally acquired by a missionary John Steele who lived and taught for many years in Swatow. Wang’s PhD thesis contains a useful overview of the scholarly literature around this text.

Below we reproduce the text of the song, with transcription in modern pronunciation (based on Zeng, 1991; we don’t exactly know the historical pronunciation) and a translation into English.

Further reading:

- Digitized version of the 1566 edition of 荔鏡記, on the page with this song

- Full text version with notes, and recording of recitation in Taiwanese Southern Min

- 曾憲通(1991)「明本潮州戲文所見潮州方言述略」《方言》1991年第1期,10-29

- Wang Yibo (2019) Liyuan opera Lizhiji : New materials, stories, and insights. PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh.

無ㄙ歌 bho5bhou2 gua1 “The Wife-less Man’s Lament”

拙年無ㄙ,

zua3(5)ni5 bho5(7) bhou2

These past years I’ve had no wife,

拙年 zua3(5)ni5 - in these past years (cf. Zeng, 1991, pg. 21)

守孤單,

siu2 gu1duan1

and have kept my watch alone,

清清冷冷無人相伴。

cêng1cêng1 nên2nên2 bho5 nang5 siê1puan6

cold and empty without someone by my side.

日來獨自食,

rig8lai5 ga1gi7 ziah8

In the day, I eat alone,

獨自 - could be a semantic borrowing (訓讀) for ga1gi7 (usually written as 家己); otherwise 獨自 would be pronounced as dog8ze6

冥來獨自宿。

mê5lai5 ga1gi7 suah4

at night, I am quartered alone.

行盡暗臢路,

gian1zing6 am3sam3 lou7

I walk through a dark and filthy road

暗臢 am3(5)sam3 (phonetic borrowing, cf. Zeng 1991, pg. 16)

踏盡狗屎乾,

dah8zing6 gao2sai2 gin5

and step in a pile of dog shit.

盤盡人後牆,

buan5zing6 nang5 ao6ciên5

When scaling over someone’s back wall,

盤牆 buan5ciên5 - to scale a wall; 盤 likely a phonetic borrowing (cf. Zeng 1991, pg. 18)

屎肚都蹊破。

sai2dou2 dou1 koi3pua3

I get struck hard in the abdomen.

屎肚 sai2(6)dou2 - abdomen

乞人力一着,

keg4 nang5 liah8zêg8dioh8

When I get caught,

力 - phonetic borrowing for 掠 liah8 “capture”, modern pronunciation is lag8

鬃仔去一半。

zang1gian2 ke3 zêg8buan3

I lose half my hair.

丈夫人無ㄙ,

da1bou1nang5 bho5 bhou2

A man without a wife

親像衣裳討無帶;

cêng1ciên6 i1siang5 to2 bho5 dua3

is like a gown without a belt.

諸娘人無婿,

ze1niê5nang5 bho5 sai3

A woman without a husband

恰是船無舵;

kah4 si6 zung5 bho5 dua6

is like a boat without a rudder,

拙東又拙西,

zua3dang1 iu7 zua3sai1

aimlessly jerking to the left and right

拙了無依倚。

zua3liao2 bho5 i1ua2

with nothing to rely upon.

依倚 - to rely upon

人說一ㄙ強十被,

nang5 suêh4 zêg8bhou2 giên5 zab8puê6

People say that a wife is worth more than ten good blankets,

強 - pronounced giên5 when meaning “better than” (otherwise kiang3 to mean “strong”)

十被甲也寒。

zab8puê6 gah4 ia7 guan5

but even when covered with ten blankets I am still cold.

Posted on 2021-06-29 00:00:00 +0000